Biomass-fired thermal networks – the greenwashing of Switzerland

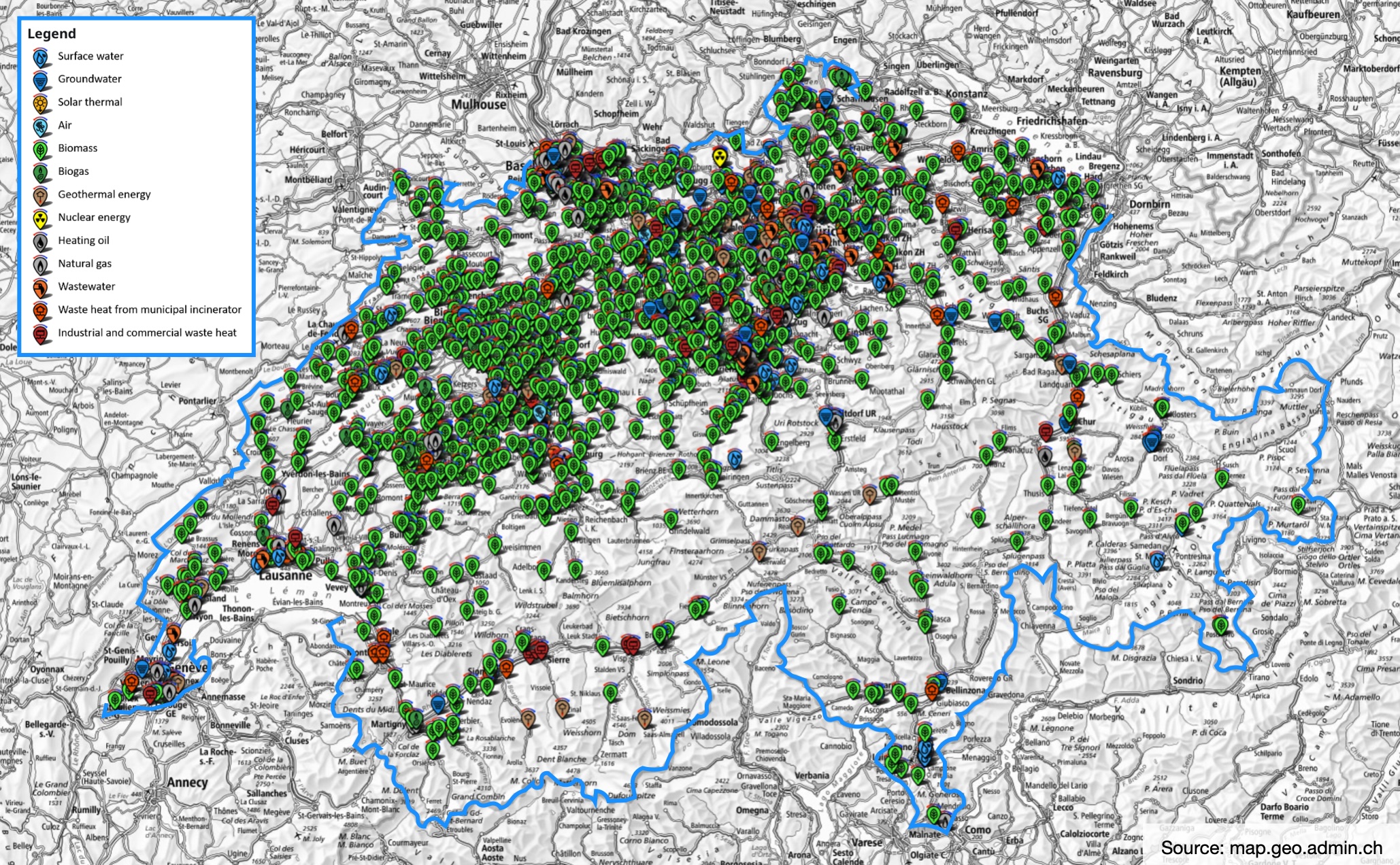

Take a look at the map of Swiss thermal networks

The country is tinted a reassuring shade of green, with a verdant band across the central Plateau from Geneva in the SW to Lake Constance in the NE.

Thermal networks supply thermal energy in the form of water or steam generated from a central plant to a number of separate buildings via a system of underground pipes. They include district heating, local heating and even district cooling networks. Output ranges from 100 kW to over 1GW and while only 43% are powered by renewables, these systems are largely characterised by their “low CO2 emissions”, or so officials claim, and Switzerland is banking on them to help reach net zero and energy independence.

But these goals come with costs and controversy.

Thermal networks are plagued with exorbitant connection, construction and maintenance fees which are passed on to consumers. Laying underground pipes results in roads and neighbourhoods being dug up and disrupted. Critics also bemoan a lack of transparency, local monopolies that prevent consumers from switching providers and the fact that gas and Waste-to-Energy (WtE) plants power many networks, arguably undermining green claims.

Despite this, district heating consumption increased by 9.2% in 2024 and the current 1,400 or so networks (some 9TWh) are expected to double (to 18TWh) by 2050, to provide 40% of all hot water and heat needs by mid-century.

And therein lies another problem. Look at the map again.

The preponderance of green derives from biomass (light green) and biogas (dark green) installations which make up around 70% of the total. But whereas biomass-fired systems dominate in terms of numbers, 40% of heat is supplied by WtE plants (which also burn up to 33% wood). If Switzerland’s thermal network is to double by mid-century, chances are many of the additions will be biomass-fuelled. A whopping 85% of biomass already comes from wood. And the country’s woody biomass potential has already been largely utilised or even exceeded, as is the case in the canton of Zurich.

In 2024, 75% of all deciduous wood harvested was burnt and woodchip consumption in general was up 3% from 2023 thanks to the rapidly growing network, with demand increasing in the Alps (+8%), Jura (+5%) and Pre-Alps (+1%), according to a Federal Office for the Environment press release (english, short version)

Only a tiny fraction of woody biomass can be sustainably harvested and what is extracted should be used to replace fossil fuels in high-temperature industrial processes. Precious hardwoods and whole trunks have no business going up in smoke to heat homes.

To avoid repeating the extractive errors of the fossil sector, we must prioritise the foundational social and environmental values of forest ecosystems as well as a framework that allocates biomass to high-value applications first.

If we don’t, Switzerland’s map of thermal networks could start looking very green around the gills.

January 2026